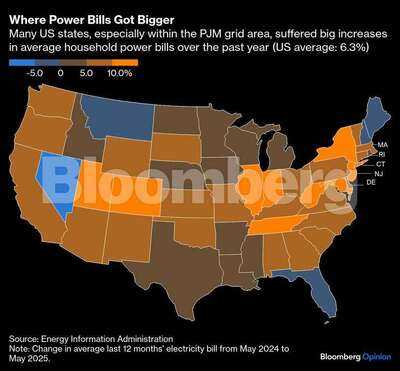

Silicon Valley, powerful as it is, should be wary of ticking off 67 million Americans.PJM Interconnection is a regional transmission organization that manages the biggest electricity grid in the US, covering all or part of 13 Midwestern and mid-Atlantic states plus the District of Columbia. In all but four of those states, plus DC, average annual power bills in the year through May increased faster than the national average, which was eyewatering in itself at over 6%.

Plug prices, rather than pump prices, are igniting a political firestorm. In New Jersey, the latest flashpoint, utility bills figure prominently in a gubernatorial race that has gained national attention and is less than three months from election day. And at the heart of all this is the race for artificial intelligence.

New Jersey residents, whose 13.3% bill increase was the third-highest in the US, can perhaps draw some comfort from New York faring worse, where bills surged 14.4%. More pertinently, 94% of the increase in PJM wholesale power prices — which cover generation and transmission but not distribution charges — through May related to the energy component according to Monitoring Analytics, the grid’s independent market monitor. That element, mostly related to natural gas prices, should level off or even decline.

New Jersey residents, whose 13.3% bill increase was the third-highest in the US, can perhaps draw some comfort from New York faring worse, where bills surged 14.4%. More pertinently, 94% of the increase in PJM wholesale power prices — which cover generation and transmission but not distribution charges — through May related to the energy component according to Monitoring Analytics, the grid’s independent market monitor. That element, mostly related to natural gas prices, should level off or even decline.

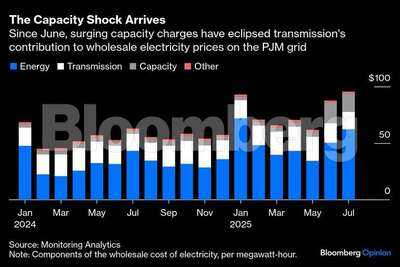

Now for the bad news: These residential billing data only run through May. That was just before the impact of a monumental jump in capacity prices, based on an auction run by PJM last year, kicked in. This chart of more up-to-date wholesale prices shows further pain is coming.

Capacity auctions set payments to generators that encourage them to keep existing plants open or build new ones, separate from the revenue they earn for actually producing electricity. This is a crucial, if arcane, corner of the power market and its shock will stick because it gets set for a year at a time — and the latest auction, for the year beginning June 2026, came in even higher.

After many years of flat electricity demand, PJM now forecasts an imminent jump, and it takes time — as well as spiking price signals — for energy supply to react. The culprit is the AI boom, with PJM serving Virginia’s burgeoning data center alley. Some 64% of those ballooning capacity payments that began hitting bills in June relate to actual and projected datacenter demand, according to Monitoring Analytics’ calculations.

The latest auction, high as it was, was actually capped after Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro complained. But price caps merely relieve symptoms and do nothing for the underlying condition.

The latest auction, high as it was, was actually capped after Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro complained. But price caps merely relieve symptoms and do nothing for the underlying condition.

The auction itself needs fixing. Hugh Wynne, utilities analyst at Sector and Sovereign Research LLC, compares it to a “rain dance” that doesn’t deliver what it is supposed to: New capacity. The inflated costs of the last two auctions are enough, by his calculation, to fund 19 gigawatts of new gas-fired capacity, yet cleared only four gigawatts of actual new additions. The result is a transfer of a wealth from homeowners mostly to existing generators for little reward.

Part of the problem is timing. Auctions are supposed to set prices several years out but delays have shortened that period to less than 12 months, completely inadequate for planning plants that take years to construct. In addition, PJM has adopted more conservative assumptions for the reliability of different types of generation. While these are shaped by the poor performance of plants during prior extreme weather events, they effectively reduce the total capacity assumed to be available, thereby driving up the auction price, and may be worth revisiting given lessons learned from those episodes.

PJM has implemented or proposed several reforms, such as expanding participation by certain types of generation. Wynne suggests splitting the capacity market into one for existing plants and another for new capacity, thereby offering more surety of pricing for the latter and, presumably, less of a windfall for the former.

Lawmakers are proposing more radical, and heavy handed, measures. Pennsylvania’s legislature is considering bills that would allow regulated utilities, which own the wires, to also invest in new power plants that would compete with independent generators. Meanwhile, New Jersey’s general assembly passed a bill directing regulators to explore alternatives including withdrawing from the capacity auction or even PJM altogether. Although it is not uncommon for politicians to lose faith in competitive energy markets at moments of stress (see California in 2002), “to unwind that clock would take a long time, likely be expensive and be fraught with uncertainty,” warns Timothy Fox, who leads power sector research for ClearView Energy Partners, a Washington-based analysis firm.

It would be absurd to abandon the benefits of decades of deregulation just to accommodate data centers; rather, the onus is largely on them. At a minimum, they should be required to effectively bring their own power, committing to long-term power purchase agreements to support new plants, not just signing contracts for existing capacity. That new capacity would increase the grid’s resilience overall, shifting datacenters from being a challenge to being part of the solution. In return, such plants could be given priority in terms of permitting and interconnection.

Training and using these models is more energy intensive than conventional internet browsing, particularly if the sort of always-on AI agent envisioned by Open AI’s Sam Altman becomes common. Yet datacenter operators have an economic incentive to become more efficient and the tools to do so. Along with bringing new hardware to the grid in the form of generating capacity, AI giants could presumably also deploy software to use that grid in smarter ways, such as those advanced by Vijay Gadepally at MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory. To a large extent, if AI is all it’s cracked up to be, it should be an energy problem that ultimately solves itself. Indeed, the building backlash in PJM indicates it must.

Plug prices, rather than pump prices, are igniting a political firestorm. In New Jersey, the latest flashpoint, utility bills figure prominently in a gubernatorial race that has gained national attention and is less than three months from election day. And at the heart of all this is the race for artificial intelligence.

Now for the bad news: These residential billing data only run through May. That was just before the impact of a monumental jump in capacity prices, based on an auction run by PJM last year, kicked in. This chart of more up-to-date wholesale prices shows further pain is coming.

Capacity auctions set payments to generators that encourage them to keep existing plants open or build new ones, separate from the revenue they earn for actually producing electricity. This is a crucial, if arcane, corner of the power market and its shock will stick because it gets set for a year at a time — and the latest auction, for the year beginning June 2026, came in even higher.

After many years of flat electricity demand, PJM now forecasts an imminent jump, and it takes time — as well as spiking price signals — for energy supply to react. The culprit is the AI boom, with PJM serving Virginia’s burgeoning data center alley. Some 64% of those ballooning capacity payments that began hitting bills in June relate to actual and projected datacenter demand, according to Monitoring Analytics’ calculations.

The auction itself needs fixing. Hugh Wynne, utilities analyst at Sector and Sovereign Research LLC, compares it to a “rain dance” that doesn’t deliver what it is supposed to: New capacity. The inflated costs of the last two auctions are enough, by his calculation, to fund 19 gigawatts of new gas-fired capacity, yet cleared only four gigawatts of actual new additions. The result is a transfer of a wealth from homeowners mostly to existing generators for little reward.

Part of the problem is timing. Auctions are supposed to set prices several years out but delays have shortened that period to less than 12 months, completely inadequate for planning plants that take years to construct. In addition, PJM has adopted more conservative assumptions for the reliability of different types of generation. While these are shaped by the poor performance of plants during prior extreme weather events, they effectively reduce the total capacity assumed to be available, thereby driving up the auction price, and may be worth revisiting given lessons learned from those episodes.

PJM has implemented or proposed several reforms, such as expanding participation by certain types of generation. Wynne suggests splitting the capacity market into one for existing plants and another for new capacity, thereby offering more surety of pricing for the latter and, presumably, less of a windfall for the former.

Lawmakers are proposing more radical, and heavy handed, measures. Pennsylvania’s legislature is considering bills that would allow regulated utilities, which own the wires, to also invest in new power plants that would compete with independent generators. Meanwhile, New Jersey’s general assembly passed a bill directing regulators to explore alternatives including withdrawing from the capacity auction or even PJM altogether. Although it is not uncommon for politicians to lose faith in competitive energy markets at moments of stress (see California in 2002), “to unwind that clock would take a long time, likely be expensive and be fraught with uncertainty,” warns Timothy Fox, who leads power sector research for ClearView Energy Partners, a Washington-based analysis firm.

It would be absurd to abandon the benefits of decades of deregulation just to accommodate data centers; rather, the onus is largely on them. At a minimum, they should be required to effectively bring their own power, committing to long-term power purchase agreements to support new plants, not just signing contracts for existing capacity. That new capacity would increase the grid’s resilience overall, shifting datacenters from being a challenge to being part of the solution. In return, such plants could be given priority in terms of permitting and interconnection.

Training and using these models is more energy intensive than conventional internet browsing, particularly if the sort of always-on AI agent envisioned by Open AI’s Sam Altman becomes common. Yet datacenter operators have an economic incentive to become more efficient and the tools to do so. Along with bringing new hardware to the grid in the form of generating capacity, AI giants could presumably also deploy software to use that grid in smarter ways, such as those advanced by Vijay Gadepally at MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory. To a large extent, if AI is all it’s cracked up to be, it should be an energy problem that ultimately solves itself. Indeed, the building backlash in PJM indicates it must.

You may also like

Ola vs TVS: New TVS Orbiter Electric Scooter Set to Undercut iQube, May Challenge Ola S1X

Coronation Street star wows in bikini after huge personal news

WhatsApp Introduces Voicemail Feature: Now Send a Message After a Missed Call

US Open match halted as umpire and both players 'destroy the court' hunting lost item

Coinbase CEO Warns: “Adopt AI or Lose Your Job” – Engineers Fired for Resisting AI